Today is the last day of the OSF season. Today is the last day of THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST. Today is Heather’s last day as Gwendolyn. And as big a day as that is for me (she's coming home) - selfish me, it’s an even bigger day for her.

Today is the last day of the OSF season. Today is the last day of THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST. Today is Heather’s last day as Gwendolyn. And as big a day as that is for me (she's coming home) - selfish me, it’s an even bigger day for her.See, Heather didn’t just come to Ashland for the first time as an actress.

She was born there. Raised there. Her mother, a single parent school teacher, in a valley that was home to a unique thing started by Angus Bowmer many many years ago.

For the last two years (and the last three of four), she has lived the dream she had as a girl – to be up in the lights, on the boards, in the place where she was first introduced to theatre. First fell in love with it.

Few of us are destined for such things.

*****************

The first time I heard Heather's voice, it was over the phone. An ex-girlfriend I was still on good terms with had been an acquaintance of Heather's in college. When I was accepted in Columbia's graduate MFA program, this ex told me that Heather might have an apartment I could sublet.

The voice at the other end of the phone had some depth to it, but was cheerful. And the mind it was attached to was funny; the soul fair and sensitive.

"Think of a clown car. Without wheels," she said, describing the place.

"A clown car? Well, how small is it?"

"It's about 5 and a half by 9."

"Uh, pardon me?"

"5 and a half by 9."

5 and a half by 9? I walked around in my rather spacious San Francisco office, skeptically thinking that nothing could be that size and lived in. I'd heard of coffins that were bigger.

"But it's a block from Central Park," she added with some chirp - as if my enthusiasm had waned. But it hadn't. She was simply hearing my mind come to the decision that she was dimensionally challenged. That was the only possible explanation for her quote. There was just a little too much pause though, so she went on: "And it's only $630 a month."

"But it's a block from Central Park," she added with some chirp - as if my enthusiasm had waned. But it hadn't. She was simply hearing my mind come to the decision that she was dimensionally challenged. That was the only possible explanation for her quote. There was just a little too much pause though, so she went on: "And it's only $630 a month."Having concluded that she didn't understand the difference between and inch and a foot, I was sure it was a steal. "Great. It's mine. Don't even think about renting it to anyone else."

It did turn out to be a steal, though I wasn't really to find out why for another year and a half. It also turned out that her clown car description was charitable.

When I arrived in NY four months later, I called to set up a time to see it. She insisted on this, feeling that before I wrote a check for it, I should understand just exactly what I was in for. Apparently she knew I didn't think she could measure space for shit.

After repeating her "It's small" warning, she warned me about something else, too, though. "Now, look," she said, "Before you come over, there's one other thing - the place is going to smell like pot, but it's not me. I don't smoke. My acupuncturist comes before you do and he burns moxie, so...."

"Don't worry," I reassured her, "I'm sure you're not a doper." And then I thought, no wonder she doesn't know how big her apartment is, she's stoned.

My suspicions about her devotion to magazines like High Times were confirmed on my way up to her place (it was a 3 floor walkup). I hit a wall of dope smoke so thick on the second landing I thought the place had to have been built in Jamaica.

Jesus, I thought, maybe she's actually growing plants in there.

And just as I was about to answer my own question, the door to 3a opened and I felt something wonderful happen: there before me, in the tiniest, moxie-smoke filled, apartment in New York was a beautiful blue-eyed, petite redhead wearing an untucked blue oxford shirt and a grin that said: See, it's a lot smaller than you thought, and it really is moxie-smoke, you idiot.

She had to step aside for me to get in.

It took less than three seconds to look at all of it. It had a loft bed and a mini-bar refrigerator. The bathroom made airplane toilets look like McMansions. It was too small even for a cockroach.

"I told you."

"Uh, yes, yes you did."

"Still want it? I'll understand if you don't."

"Uh...."

"Why don't we talk about it over coffee at the diner around the corner."

With that visit, and over that coffee, I realized that she was not a stoner. Not dimensionally challenged. Oh, no. In fact, if anything she was about as grounded and real as they get. And she was even funnier in person than she was over the phone.

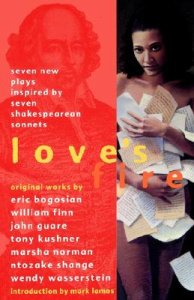

Her story was not so simple however. Having grown up in Ashland, she'd always wanted to act. In the early 90s she took a giant step in that direction when she was accepted into the NYU graduate acting program. After NYU, she joined The Acting Company (of Houseman-Kline-Streep fame) and did LOVE'S FIRE in London, New York, etc. Two years later, she started working regionally - The Guthrie being one of the bigger places - doing Shaw, Ibsen and good old Bill, as well as some contemporary stuff. I was catching her after an illness had brought things to a halt and she was trying to decide if she wanted to continue acting. The recent year had been tough - and as if to make things worse, her grandmother in Ashland was in failing health. Should she give up her NY apartment?

Her story was not so simple however. Having grown up in Ashland, she'd always wanted to act. In the early 90s she took a giant step in that direction when she was accepted into the NYU graduate acting program. After NYU, she joined The Acting Company (of Houseman-Kline-Streep fame) and did LOVE'S FIRE in London, New York, etc. Two years later, she started working regionally - The Guthrie being one of the bigger places - doing Shaw, Ibsen and good old Bill, as well as some contemporary stuff. I was catching her after an illness had brought things to a halt and she was trying to decide if she wanted to continue acting. The recent year had been tough - and as if to make things worse, her grandmother in Ashland was in failing health. Should she give up her NY apartment? Well, since she didn't know, renting it to me seemed like a good way to buy some time while the answer made itself clear.

"I have a short play in Atlanta and then l go back to Ashland and take care of Grandma Rie," she told me.

"I won't leave you in the lurch" I said. "Are you sure you don't want anything to eat?"

"No, thanks, though."

I frowned at her. She'd only had a glass of water.

"I'm really not hungry."

"Okay," I said, "But next time I see you, lunch is on me."

And I meant it - she seemed like someone I wanted to know.

*************

I moved out 11 months later. In those months, however, I had felt that in some ways, she had been like a roommate to me. I had lived with her stuff in the apartment. Ate off her plates. Read some of her Shakespeare editions. And managed to break, and replace, her stereo.

I moved out 11 months later. In those months, however, I had felt that in some ways, she had been like a roommate to me. I had lived with her stuff in the apartment. Ate off her plates. Read some of her Shakespeare editions. And managed to break, and replace, her stereo. We had also been drawn closer together over the phone by events: She went to Hotlanta on the morning - and I moved in on the evening - of Sept 10, 2001.

So, when she came back to NY in November of 2002, I thought I should make good on the promise to pick up a meal between us. Plus, I wanted my security deposit back.

Finding a time we were both available wasn't easy. She was spending a lot of her days out in Connecticut helping some friends with some very difficult family problems and I was experiencing a lot of doubt as a writer in my second year of grad school.

But somehow, just before Thanksgiving, we managed to figure out a way to see a movie together. It was very cold that night and we were both pretty well bundled when I met her outside Harry's Burrito place at 71st and Columbus. There was a part of me, based on our phone calls and our one previous meeting, that hoped maybe this was some sort of quasi-date and I took it as a good sign when I noticed she was wearing lip-gloss and a new pair of cowboy boots.

Unfortunately, the movie we saw was Roger Dodger. Definitely NOT a first date, or maybe any kind of a date, movie.

Afterwords, I tried to salvage the situation. I mean, I liked talking to her. My problem was, well, I didn't drink, so that kind of thing was out of the question.

"Listen, um, would you like to stay out just a little later with me. Maybe get some coffee and pie?"

She looked a little stunned and then a big grin crossed her face. "Pie?"

I looked back at her. "Yes."

(Pie? Yes. These are the words that are inscribed on the inside of my wedding ring. Inside hers is the address of the apartment where we first laid eyes on each other.)

(Pie? Yes. These are the words that are inscribed on the inside of my wedding ring. Inside hers is the address of the apartment where we first laid eyes on each other.)Within several months, I knew she was the one, but in the beginng of February 2003, she returned to Ashland where she appeared in Nilo Cruz's Lorca In A Green Dress - his first big production following his Pulitzer. We kept our relationship alive over the phone and through long visits (one of the benefits of being a grad student) and I got to know Ashland, and her, and her mother.

I also got to know just what acting meant to her, how much she loved it, and how much it loved her.

I convinced her to return to NY when the 2003 season was over, but I knew that if I was to really keep her, that I would have to share her with the stage. Particularly that stage.

I could only hope that the call would come later, rather than sooner, in our life together.

Of course, it came sooner. In July, she was offered the part of Leticia in The Belle's Stratagem for the 2005 season. I proposed in August. We got married in May 2005. It was an extra-ordinary year for both of us.

She, well, she burned up the boards on the Bowmer and was, to her happy surprise, asked back for another season to play Gwendolyn. She told me she would turn it down for our marriage, but I couldn't let her do that. I knew how much she loved acting - and how rare it was to work in a place with such a long contract on such genuinely good terms. Plus, she was a hometown favorite (still is, actually). The best anology I can think of is to imagine a little kid who grows up playing stickball in the shadows of Wrigley Field finding his way onto the pitching mound when he grows up.

She, well, she burned up the boards on the Bowmer and was, to her happy surprise, asked back for another season to play Gwendolyn. She told me she would turn it down for our marriage, but I couldn't let her do that. I knew how much she loved acting - and how rare it was to work in a place with such a long contract on such genuinely good terms. Plus, she was a hometown favorite (still is, actually). The best anology I can think of is to imagine a little kid who grows up playing stickball in the shadows of Wrigley Field finding his way onto the pitching mound when he grows up.Besides, I hated New York. I'd taken a job in advertising to pay off the MFA loans, but really just, well, you know. Then, too, the agency I worked at didn't seem to dig what I wrote. As time wore on, I realized that I was more interested in pursuing televsion and film in LA - and doing theatre on the side - than hanging around Gotham and its daily dose of bristling hostility. And I could do advertising, something that could be a lot of fun, anywhere.

After Heather was asked back, it seemed clear that I should move out West and really go for it.

Then, to prove a point at the office - and out of sheer spite - I shot some TV spec spots on my own in response to a marketing problem. When the client, Nokia, saw the ads, they bought them immediately and I was stuck in NY just when I thought I was going to escape. Eventually the campaign was inducted into the MOMA archives, but the work meant that Heather and I were to be separated for almost another whole year.

And now we are at the end of that year.

And while Heather will do school tour (teaching and performing Shakespeare in schools under the Festival's name) for a few weeks, for her, it's a conclusion to a childhood dream. For me, it's a true end to the separateness that had come to define my New York life (eventhough I am already in LA, that is one aspect of NY that followed me).

For both of us, though, today is the beginning of something that started 5 years ago when I picked up a phone, dialed a number and said: "Hi. My name is Malachy Walsh and I hear you might have an apartment for rent."